Sample Chapter: Reporting on the Northern Fury world of 1992

22 May, 2018 | General News

_This sample chapter from early in Northern Fury: H-Hour, introduces one of our key characters, the *New York Times _reporter Jack Young, and helps describes how the alternate history Northern Fury word of 1992 differs from our own reality in which the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991 after the failed August Coup. We use the device of an article Jack is writing to give a quick snapshot of the uneasy geopolitics that grow out of a resurgent Soviet Union. The pictures and maps in this blog post will obviously not appear in the book. *

0805 EST, Monday 2 November 1992

0305 Zulu

Times Tower, New York City, New York, USA

“You moonlighting for other employers now?” The almost-unfriendly challenge was offered in a nasally New York accent.

Jack Young, rising star foreign affairs reporter for the New York Times, felt his pulse quicken. The advance copy of next month’s The Atlantic had finally landed on his untidy desk, shoehorned at the margins of the buzzing, cubicled newsroom floor. Seeing his name on the front cover of a publication always thrilled him. Jack looked up from the magazine to his pudgy, spectacled editor who was peering down at him with a mixture of amusement and annoyance.

“Not moonlighting, Bill, just practicing my craft,” said Jack with his typically disarming grin. “Doing my part to make the Times look good.”

“We’d rather you do that in the pages of the Times,” retorted Bill half-heartedly.

“I know, I know,” Jack said, raising his palms in mock surrender, “but the article was too long for even a Sunday edition, remember. You said so yourself.”

Bill waved one hand dismissively. “Is that article on the President’s relationship with the Russian president ready? I want to run it tomorrow.”

“Trying to swing the election, are we?” teased Jack.

Bill scowled in return. The editor didn’t have much of a sense of humor.

“It’s right here. I’m just making my final edits and I’ll walk it over.” Jack tapped his screen.

“Make sure it’s not late,” Bill warned as he turned to walk back to his office. Then the older man paused. “And Jack?”

“Yeah Bill?” Jack said, looking up.

“Good work on that Atlantic piece.” Bill said, before stomping off, annoyed by the sliver of humanity he’d just shown.

“Thanks,” Jack said to his back, surprised, but grinning again.

As the editor disappeared into his windowed office, Jack leaned back. He loved being a reporter, but sitting here at his desk Jack knew that he cut a far different figure from his colleagues around the newsroom floor. Instead of a cheap suit or blazer that seemed to be the uniform for his peers, Jack wore clothes more suited for a hike in the Catskills than a stroll through the concrete canyons of Manhattan. His Land’s End collared shirt and blue jeans were distinctly out of place, and his tall, lanky frame, topped by an angular head with a severely receding hairline, made him easy to pick out even from across the newsroom.

His workspace set him apart, too. Around his desk and on the off-white wall behind his chair were taped clippings of stories and pictures he’d sent back from places like Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Iraq, Yugoslavia, the Ukraine, and Poland; testimonies to his thirst for a meaty story and, if he was honest with himself, to a certain vanity in seeing his name in print. He had another trip planned for Poland. He wanted to get closer to the simmering unrest brewing there as it tried to shake off the influence of the newly resurgent Soviet Union.

The readership of Times leaned towards the cosmopolitan, but Jack’s interests lay squarely in the drama of human conflict in the earthier parts of the world. Indeed, that interest was what had prompted him to secure funding from the Times a few weeks ago for a circuit of Eastern Europe, which had borne the fruit of the article in the magazine now on his desk.

Jack looked down at the magazine. He touched his name on the glossy cover while savoring the satisfaction of the moment. Then he lifted the magazine from his desk, flipped to the piece he had authored, and began to read:

BACK IN THE USSR?

Jack Young, reporter

As Washington prepares for a turbulent election night that will see US voters choose between “it’s the economy, stupid,” or “who’s going to stand up to the Soviets?”, now would seem a good time to take a step back and take stock of the truly stunning reversals to the revolutions of 1989 that have taken place in the USSR and its sphere of influence over the past eighteen months. A year-and-a-half ago the Soviets showed every sign of relinquishing their control over the states of the now defunct Warsaw Pact and withdrawing into their heartland to lick their economic and social wounds. Today, however, they are reasserting their dominance in ways more reminiscent of 1968 than the heady days of 1991.

Indeed, since the August 1991 coup, the USSR’s charismatic new leader, Pavel Medvedev, has presided over a stunning and unlikely re-emergence of Soviet geopolitical and military power. How has he accomplished this turnaround, and what are its implications for European and global security in the near future? The man who takes over in the Oval Office next January would do well to consider these questions.

Jack noted with satisfaction that his photo of the stocky Russian leader reviewing this year’s May Day Parade in Red Square headed the next section.

Pavel the Terrible

In the turmoil that followed the August Coup, the hard-line administration of Pavel Medvedev and his clique seemed ready to collapse under the weight of the same pressures which had prompted the previous and now deposed Soviet government to institute Perestroika and Glasnost*. The Soviet economy was sputtering, the military appeared demoralized and inept following the withdrawal from Afghanistan, and republics of the Union appeared ready to declare their independence from Moscow—indeed, some already had.*

Medvedev moved quickly to quash these stirrings by renouncing the New Union Treaty and sending troops into the Baltic republics to assert Soviet control in a short, violent campaign. The nationalist movement in Ukraine, however, proved more difficult to defeat. Here the Soviet president was forced to bring in troops from as far away as Siberia, with the bloody results broadcast to the world from Kiev this spring.

A photo that Jack had taken during the violence in the Ukrainian city emphasized the point. It showed a T-72 on the bloody pavement of Kiev’s October Revolution Square with a score of bodies lying in the background.

Independence movements in the Central Asian republics failed to coalesce after the grim resolve Moscow had shown in the West. Even so, separatists in the Transcaucasus region, particularly the Georgian Republic and its neighboring areas, are still a sore spot for the Soviet administration.

Within the Russian Republic, Medvedev has cracked down on political opposition with a skillful combination of soft and hard power, complementing the violent purges which followed hard on the heels of the August Coup. Medvedev has used the Soviet justice system to make spectacular examples of several opponents who were incautious enough to oppose him while engaging in real corruption elsewhere. Several prominent opposition politicians have ended up in the labor camps that form the bulk of the Soviet penal system, and one district governor was executed for misappropriating state funds. Perhaps most stunning of all was the fall of the KGB chairman and his replacement with a Medvedev loyalist. All in all, Medvedev seems to have pulled the USSR back from the brink of political dissolution and set it on a more stable social footing.

Military Reform

Part of the key to understanding Medvedev’s success has been his complex relationship with the Russian military. Army support for the August Coup, we have learned, was in no way assured. We may never know how close the Red Army came to intervening on the side of the sitting government in those chaotic days. Nevertheless, Medvedev quickly won the support and then the loyalty of his generals and admirals by committing the Russian economy to modernizing and expanding Russia’s conventional forces. The fact that the Soviet president’s two sons serve as officers in the Soviet military, one in the navy and another in the elite parachute forces, has no doubt strengthened his hand.

To illustrate this, Jack had included a photograph of the Russian president grasping the shoulders of his two sons. The older son wore in the blue uniform of a naval officer, while the younger was dressed in the fatigues, striped undershirt, and blue beret of a Soviet paratrooper. The genuine pride on the face of the father told the story nicely, Jack thought.

Cuts to Soviet conventional forces under the previous Soviet president have been reversed, and an aggressive naval build-up has kept Soviet shipyards busy year-round. In return, the military has supported Medvedev’s reform of its ranks. Corrupt or incompetent officers have been purged and even executed in some cases. The brutal practice of "_dedovshchina," in which experienced conscripts ruthlessly hazed new inductees, has apparently been abolished. Beyond simply upgrading and purchasing new weapons, the Soviet defense establishment has put enormous efforts towards improving the living conditions, pay, and morale of its soldiers, and towards professionalizing some of the junior enlisted ranks. Outside defense observers have noted significant improvements in the morale and efficiency of a force that just last year appeared to be on the verge of impotence. Today, the Soviet military’s support for Medvedev is unquestionable._

Now, Russia’s conventional forces—ground, naval, and air―appear more powerful than at any time since the Brezhnev era. While President Medvedev’s government appears to have honored all standing treaties regarding the reduction of nuclear weapons, its relationship with the Conventional Forces in Europe Treaty has been more contentious. Whether the Soviets can sustain this force structure for the long term remains to be seen.

It’s the (Russian) Economy, Stupid!

A photo of drably-clothed civilians lined up to buy bread in Tallinn was inset into the following section.

One of Medvedev’s greatest accomplishments has been to turn the anger of the Soviet people at their difficult economic conditions outward towards the West. Indeed, Western leaders have played into Medvedev’s hand by the punitively ham-handed ways in which they have imposed economic sanctions on the USSR, punishing Russia for the violence in Poland while ignoring the excesses of the pro-Western faction in that country’s internal turmoil. While one can never really tell in a society as secretive as that of the Soviet Union, all indications are that the Soviet people have wholeheartedly bought into Medvedev’s vision of a rejuvenated USSR, as well as his antagonism towards "NATO encirclement," economic and otherwise.

The Soviet ‘Near Abroad’

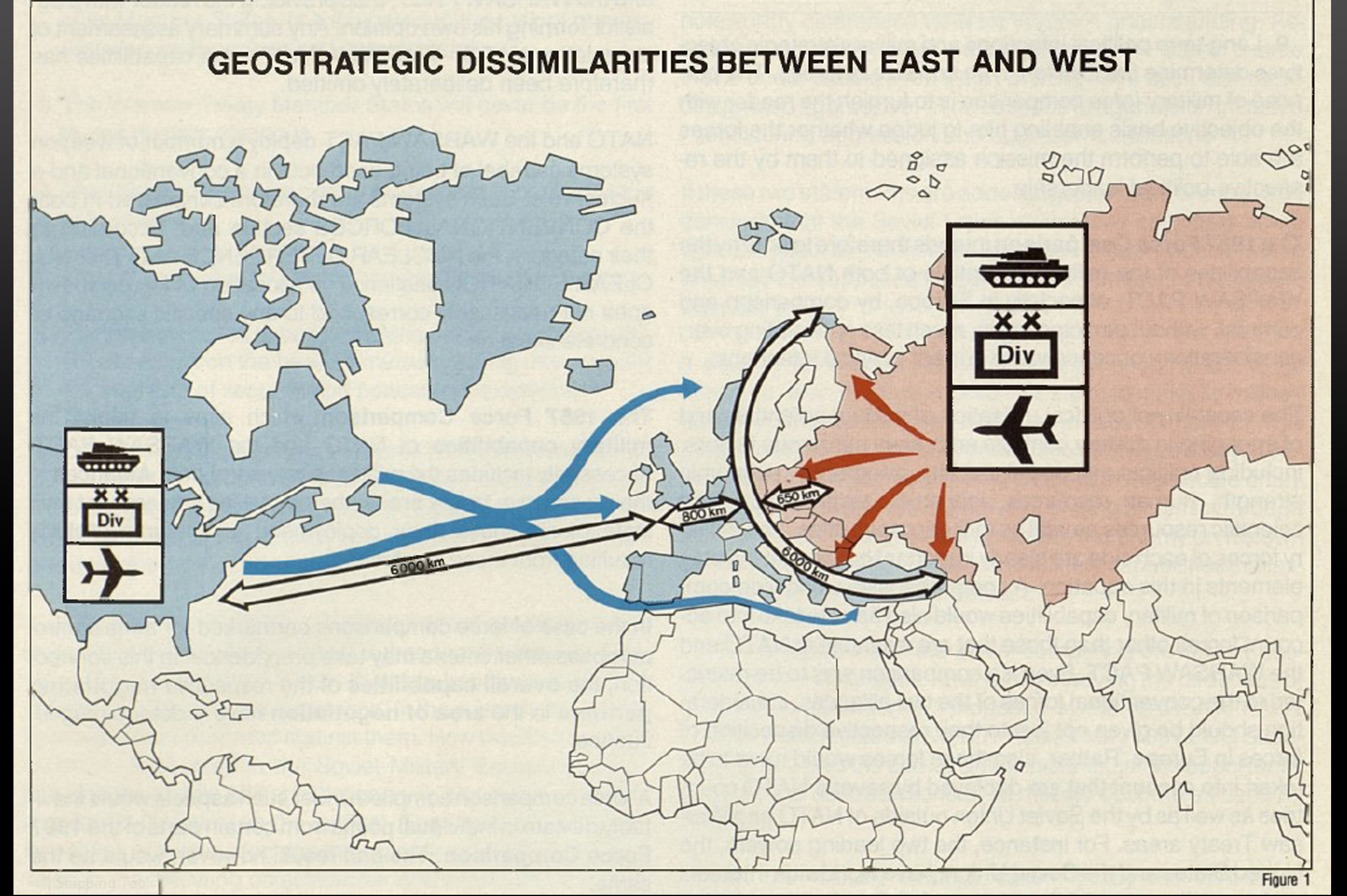

Here Jack had included a map of Central Europe.

From the perspective of Western leaders, the most troubling aspects of Medvedev's foreign policy are the USSR’s destabilizing influence in the ongoing chaos in Poland. There, the Solidarity government has apparently failed to solidify its role as a popular governing force. This is due no doubt in part to Soviet interference but also to that government’s inability to bring some of the former communist regimes more notorious figures to trial, as well as the Red Army’s de facto military occupation of the socially and ethnically fractured Czechoslovakia.

In Poland, the Soviets have practiced a sort of hybrid engagement, offering material support and even military “volunteers” to the pro-communist and pro-Moscow factions on the one hand while vociferously denying any involvement on the other and condemning the excesses of what they call “The regime in Warsaw.” Every faction in the Polish quagmire has been guilty of excesses on some level, but it has been the Russian influence that has kept it in simmering chaos for the past year. The Polish state may suffer political and cultural fracturing akin to what is occurring further south in Yugoslavia.

The Czechoslovak situation is much different. As chaos spread in Poland the Soviet Union negotiated the rights to withdraw their forces in the former East Germany through Czechoslovakia, citing concerns that the conflict in Poland could jeopardize the Baltic and Polish routes. The Czechs were no doubt surprised when they realized that the Soviets understood the agreement as allowing them to withdraw their forces to the former Warsaw Pact country rather than through it. By the time the Czechoslovak government understood what was happening they were essentially presented with a fait accompli by Medvedev: accept Soviet “protection” or be subject to whatever coercion thousands of Soviet troops already present could exert. Since then the Soviets have skillfully played upon social divisions between Czechs and Slovaks to forestall any meaningful resistance to their occupation. Today, Czechoslovakia is an armed camp, a Soviet dagger in the heart of Central Europe, containing almost all the forces that had been present in the former East Germany along with those that never left Czechoslovakia.

The rest of the former Warsaw Pact nations have elected, more or less willingly, to remain in Moscow’s orbit. Hungary has been the most unwilling. Bulgaria and Romania have managed to overcome political unrest within their own borders, reportedly with Soviet assistance, and repress or at least counterbalance their more progressive elements. The effect has been to provide Medvedev with badly needed allies as much of the rest of the European community has nominally turned against his country.

Wherefore art thou, NATO?

In the heady days after the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact and the seemingly impending implosion of the USSR, many pundits questioned whether there would be any need for NATO in a post-Cold War world. Pavel Medvedev himself answered these doubts when he categorically denounced his predecessor’s Helsinki Declaration that Moscow would not interfere in the affairs of eastern European nations and instead demanded the withdrawal of a reunited Germany from the Atlantic Alliance as a precondition of Soviet withdrawal from their erstwhile allies’ territory.

The alliance certainly has renewed purpose; however, many of its sixteen long-standing member states have chosen to pursue “peace dividend” cuts to their militaries as if the Cold War had actually ended. Even the mighty United States, secure in its military superiority following the fireworks of the Persian Gulf War, has seen fit to slash its commitments in Europe and reduce the size of its ground forces there, though the US president has so far managed to forestall cuts to the Navy and Air Force budgets. France remains a vociferous element in NATO’s political branch, but has so far continued in its status as a “non-military” member of the Alliance, though the French military has maintained much of its Cold War force structure. Other member states have made or are planning far deeper cuts to their conventional war-making capabilities, with the Norwegians being the one notable exception. These cuts, while they have freed up significant funds for social programs, have weakened NATO’s hand against the Russian leader.

Germany, in particular, has been balancing their imperative to remain within the Alliance with their desire to placate Soviet fears and appease leftists within their own country who have been demanding an end to collective security. Accordingly, the Bundeswehr has faced more severe cuts than any other NATO military. To date these cuts have failed to elicit any softening of Moscow’s demands for a German withdrawal from NATO.

Here a colored graph showing reductions in the numbers of each NATO members’ armed forces, broken down by troops, tanks, artillery, aircraft, and ships, highlighted Jack’s point.

These cuts stand in stark contrast to the economic stick that Europe and America have been willing to wield to express their displeasure at the USSR’s actions in its independence-minded republics and in Eastern Europe. Sanctions have targeted many categories of Soviet exports and imports, and while they have surely hurt the USSR’s economy, they have also prompted Russia to seek a closer trading relationship with China. These measures have certainly highlighted the economic vulnerability of the USSR’s geography. It remains to be seen if the West’s sanctions will be successful in forcing Medvedev to soften his stance against NATO and Eastern Europe. For now, they seem to have only strengthened his hand by giving him an antagonist to demonize before the Soviet people.

This leaves the West’s leaders to ponder how to best handle a resurgent Soviet Union. The apparent end to the East-West antipathy two years ago followed by its dramatic and rapid return have left many in NATO countries with a distinct “Cold War weariness,” hampering the efforts of those governments who would prefer a more firm military stance against Moscow. How has the balance of power shifted? Where will the pieces of the new Europe fall? How long can the Russian economy stand in opposition to and isolation from the West? Whoever occupies the Oval Office next January will need to consider carefully the answers to these questions. The future of Europe, and possibly the world, depends on it.