The Warsaw Pact in Northern Fury

07 September, 2018 | General News

The Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Pact (WP) came into being as a collective defence organization of countries in response to the integration of West Germany into NATO in 1955. From the perspective of the Soviet Union however, this alliance was intended, or certainly became, a method of controlling its Eastern European neighbors, and in particular their military forces. The Soviets used the alliance to counterbalance NATO throughout the Cold War, but as Europe began to change in the late ‘80s the threads that held the WP together started to unravel. The original eight member states of the WP were: Albania, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Hungary, Poland, Romania and he Soviet Union.

Other than moral and material support for socialist movements in the “Proxy Wars” that raged throughout the globe during the Cold War (Korea, Vietnam, Cuba, throughout Africa), the only armed conflicts in which the WP engaged were operations to maintain its own status-quo. The Soviet Union intervened in Hungary in 1956 to crush a revolutionary government and reinstate a compliant communist regime. The USSR and its WP allies moved again in 1968 to invade Czechoslovakia and re-establish a pro-Soviet regime there as well. Albania, the only member to not share a geographic link to the Soviet Union, considered the invasion of Czechoslovakia too heavy-handed and left the alliance directly afterward, though it remained ideologically associated with the Soviets.

Other than moral and material support for socialist movements in the “Proxy Wars” that raged throughout the globe during the Cold War (Korea, Vietnam, Cuba, throughout Africa), the only armed conflicts in which the WP engaged were operations to maintain its own status-quo. The Soviet Union intervened in Hungary in 1956 to crush a revolutionary government and reinstate a compliant communist regime. The USSR and its WP allies moved again in 1968 to invade Czechoslovakia and re-establish a pro-Soviet regime there as well. Albania, the only member to not share a geographic link to the Soviet Union, considered the invasion of Czechoslovakia too heavy-handed and left the alliance directly afterward, though it remained ideologically associated with the Soviets.

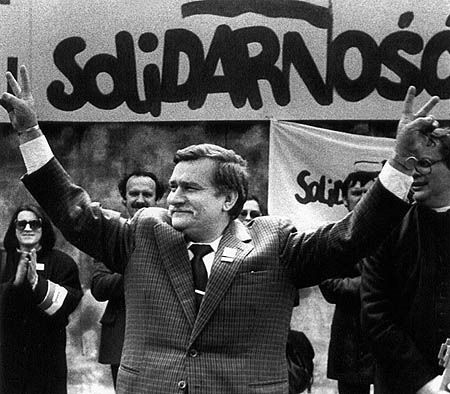

Problems really started to emerge for the WP in 1989, when Mikhail Gorbachev’s Perestroika (movement for reformation of the Communist Party) and Glasnost (openness and transparency) reforms started to take hold across Eastern Europe. The first major upheaval was a full-blown revolution in Poland in the spring and summer of 1989, resulting in the trade union Solidarity winning an overwhelming victory in a partially free election. For the first time since the end of World War II, a peaceful uprising had permanently toppled a communist regime in Europe. Poland withdrew from the WP. Many people in neighboring Eastern Bloc countries began to view the shift in Warsaw as an example to follow.

Problems really started to emerge for the WP in 1989, when Mikhail Gorbachev’s Perestroika (movement for reformation of the Communist Party) and Glasnost (openness and transparency) reforms started to take hold across Eastern Europe. The first major upheaval was a full-blown revolution in Poland in the spring and summer of 1989, resulting in the trade union Solidarity winning an overwhelming victory in a partially free election. For the first time since the end of World War II, a peaceful uprising had permanently toppled a communist regime in Europe. Poland withdrew from the WP. Many people in neighboring Eastern Bloc countries began to view the shift in Warsaw as an example to follow.

Despite the drama in Poland, the event that many thought – or hoped – was the true death knell for the WP was the reunification of Germany in 1990. Historically, the reunification of the Communist German Democratic Republic (East Germany) and the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany) started an avalanche of change; the Soviet Union dissolved in 1991, followed first by the collapse of the communist government in Hungary, then Czechoslovakia, and finally Romania and Bulgaria, who joined the revolution to shake off communist control in their countries and elect free governments. All of these events of course do not happen in Northern Fury. In our alternate history, the reunification of Germany was indeed an event that changed the political landscape of Europe, but in an entirely different way.

In the Northern Fury 1994, the WP still exists – but in a much diminished state. The Soviet Union is still the senior partner but its mechanisms for control of the lesser member states are more tenuous and less certain. Several member countries remain within the alliance, partially out of fear of the USSR’s resurgent military and economic prowess, but primarily for their own reasons:

• Czechoslovakia is essentially an armed camp. Most of the former “Group of Soviet Forces Germany” were displaced here in 1990 – and did not leave. These joined the “Western Group of Forces,” which was the designation for the Soviet Army Group that never left Czechoslovakia in our alternate history. Together, these forces boast over 500,000 Soviet troops, about 4,000 tanks, 8,000 armored vehicles and 500 aircraft, garrisoned in 400 camps and barracks throughout the country. More than any other member state, Czechoslovakia remains in the WP because it has no choice.

• Bulgaria remains in the WP because of a fear that instability in the former Yugoslavia will spill over its borders. The Soviets have provided some military and economic assistance which influences some elements in Bulgaria, but of any member, its loyalty to the Soviets is the weakest.

• Hungary is a government at odds with its people. The current regime relies on Soviet assistance, both militarily and economically to remain solvent. To a lesser extent than in Czechoslovakia, displaced Soviet forces have established residence in Hungary, causing some violent friction with many localities. Hungarian state intelligence agencies have grown substantially and are kept quite busy maintaining visibility on dissident groups, and individuals traveling into the Balkans. The border with Austria is closed.

• Romania’s dictator Ceausescu is a beneficiary of the new order in Eastern Europe. Much of the military and financial assistance that was going to East Germany and Poland is now heading to Bucharest, where the ruthless dictator has used it to prop up his faltering regime. Romania is now the staunchest ally to the Soviet Union within the WP.

• Serbia, although not a member of the WP, has been receptive to diplomatic overtures from the USSR. NATOs recent action in the Balkans is quickly driving Serbia into the Soviet camp.

• Poland is in turmoil as the Solidarity government has failed to gain control over the communist dominated Interior and Defense ministries in that country. Soviet support for the opposition to Solidarity has ensured that the country remains mired in simmering violence. The specter of direct Soviet intervention in the country adds a layer of tension, but so too does the fear that NATO countries might intervene, as they recently did in Yugoslavia. The new hardline government in Moscow refuses to tolerate any move by Poland to draw closer to Western Europe.

Each country will play a part in the coming conflict, though perhaps not the part their national governments intend.