Chapter Sample: Training

31 May, 2018 | General News

100 EST, Monday 14 June 1993

1600 Zulu

Aboard HMCS Onondaga, off Cape St. Charles, Labrador, Canada

“Up periscope.”

The burnished metal tube hissed upwards in front of Lieutenant Commander Eddie “Skip” Hughes, captain of one of the Royal Canadian Navy’s three British-built Oberon-class diesel-electric submarines, HMCS Onondaga. As the tube containing the boat’s search periscope extended to its full height, Hughes stepped forward, slapped down the handles, and grasped them at a crouch to bring his face level with the optic’s eye pieces.

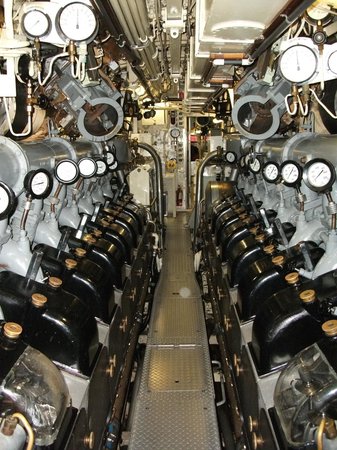

Sergeant David Strong watched the process from a kneeling position in the corridor. He was wedged between the small submarine’s banks of diesel generators, which was in the compartment aft of the cramped control room. The generators were currently silent as the submarine proceeded under the electrical power of its batteries. Strong and the three other members of his special forces team were out of their element in this environment. The only way to practice infiltrating an enemy coast from a submarine was to actually get on board a real submarine and do it. This exercise aboard HMCS Onondaga represented a culmination of the training regime for Strong and his team. It was a chance to validate themselves in the type of mission they would likely be called upon to execute in wartime. They had conducted dozens of exercises in the preceding months, but this was the first in which they would actually transfer from ship to shore.

Indeed, this was the first time since World War II that a Canadian submarine would be used for such a purpose, though in wartime they would almost certainly deploy covertly from a boat like Onondaga. Strong and his team were to become the designated experts within their JTF 2 squadron when it came to maritime deployments, and this was their first chance to exercise their skills under realistic conditions. Strong was interested in the goings-on in the submarine’s control room, having only ever experienced this sort of thing in movies up until now.

The captain hurriedly crab-walked the periscope through a full circle. Strong noticed the naval officer pause twice, mash a button with his thumb, and call out, “Northern headland, bearing three-three-zero. Southern headland, bearing two-four-three. Surface is clear.” Then the captain slapped the handles back up, stepped back, and ordered, “Down periscope.”

As the tube slid back downwards into its well, Strong saw the chief petty officer click a stopwatch and announce, “Eleven-point-three seconds, sir.”

Hughes swore under his breath and grimaced. The captain took a step, squeezing between the periscope tube and the chief petty officer to join the navigator at a small table—really, no larger than the kind of fold-down tray one would find in the back of a typical airline seat—and used a compass and protractor to plot the boat’s position.

“Five meters under the keel,” the navigator said softly.

Strong shifted his weight to his other knee and looked over his shoulder. Lined up in the corridor behind him were the three other members of his JTF 2 patrol. They were all dressed in black dry-suits with hoods pulled up over their hair and ears. The hulking frame of Master Corporal Roy looked almost comical crammed as he was between the banks of diesel generators that crowded either side of the corridor, the patrol’s gear all around his feet. Strong turned forward in time to see the boat’s executive officer step across the control room from his station by the motor control panel and say to the captain, “Sir, should we get the swimmers top side?”

The Onondaga’s hull was more akin to the submarines launched during the Second World War than the sleek cylindrical shapes of more recent designs. This did not mean that the Oberon-class boats were outdated or lacking in lethality, far from it. It did mean that the width of the sub’s control room was limited to about what one could expect from a city commuter bus, with a much lower ceiling. The Oberons were small boats, being a mere ninety meters long and less than a tenth of that in width. Indeed, the compartments available to the crew were nowhere more than four meters wide. The submarines’ designers had knowingly sacrificed creature comforts in Onondaga and her sister ships at the altar of lethality, and stealth. But even with all the noise-dampening features incorporated into the boat’s design, Sergeant Strong could hear every word spoken in the control room.

“Not yet, XO,” Hughes was saying. “We’ve got plenty of water under us, and every mile we move closer to the shore is one less our guests need to cover in an open boat.”

Hughes was a short man, stocky from too many days living inside a steel hull and enjoying good navy cooking. In the last three days at sea during their run from Halifax to the southern end of Labrador, Strong had also come to understand that the boat’s captain was supremely confident in himself, to the point of arrogance even. Now he was showing that he was aggressive, too.

“Captain,” the XO was saying in a low voice, “I feel obliged to note that the depth is going to decrease rapidly on our present course, and the charts of this area have been off before.” “Noted, XO.” The response was dismissive, but not unfriendly. “I’ve been here before. Maintain current speed and heading.”

The role of any good executive officer was to preserve the ship that he served, whereas the captain’s job was to put the ship in harm’s way to accomplish the mission. That tension was now at play in Onondaga’s control room, as Hughes pushed his command into the shallow waters of the bight to shorten the distance Strong and his crew would need to spend on the open water.

“Maintain current speed and heading, aye,” acknowledged the boat’s chief, his hand on the back of the helmsman’s seat.

Strong and his men had become familiar with the sailors in front of them over the past few days. To describe the conditions in which Onondaga’s sixty-nine crew lived as “crowded” would have been an understatement. The vessel didn’t possess even enough bunks to accommodate its usual compliment, and adding four landlubber passengers to the mix had done nothing to alleviate the strain. Even so, the navy men had been welcoming, making space for the commandos and their gear and taking time to familiarize them with the ship’s systems and operating procedures. The passage from Halifax to Labrador had been educational.

Onondaga continued throbbing slowly into the bight south of Cape St. Charles. Despite the control room’s air conditioning, Strong could see sweat beading on the temples of the navigator as he tracked the vessel’s progress with grease pencil and compass. Strong could imagine that grounding one of his nation’s precious few submarines might be a significant event in the career of the vessel’s captain and his officers. Strong’s appreciation for Commander Hughes’ guts, and his abilities, was growing by the minute.

Another moment and the navigator said in a taut voice, “Two meters under the keel.”

Hughes did not react. Now even Strong was starting to feel tense. The boat’s XO was casting sideways glances at his captain through the gaps in the sensor mast housing wells, which bisected the control room.

Now the captain ordered “Up periscope” again and repeated his earlier crab walk performance. The scans were for navigation purposes, but also to simulate a wartime check for threats in the area. They also helped the small submarine to avoid icebergs, which were still present around the Labrador coast this time of year. This time Hughes was more satisfied, both with the bearings to the landmarks and the speed with which he conducted the triangulation.

“One meter under the keel, sir,” the navigator’s voice cracked slightly as he looked up from his chart and protractor.

Hughes finally said in a calm voice, “Engines all stop. Helm, keep us level.”

The XO’s hand had been resting on the engine control dials. He quickly turned the knobs and announced, “All stop, aye,” as the massive banks of batteries housed beneath their feet stopped providing power to the boat’s two propeller shafts.

The captain turned and looked back at the four commandos kneeling in his generator room and asked, full of confidence and apparently oblivious to his XOs nerves, “Sergeant Strong, are your boys ready?”

Now came the part they had been rehearsing all morning. Strong felt the soft throbbing of the sub’s propulsion cease as he stood and responded, “Ready, Captain.”

Hughes nodded. Then he turned back and ordered, “Helm, five degrees up on the planes. Surface the boat.”

“Five up. Surfacing, aye.”

Strong felt the deck beneath him take on a slight incline. Then it began to roll slightly. A terse “Let’s go” had his team turning around in the cramped space, facing aft. A sailor in a heavy rain slick was at the rear of the compartment, his hands on the lever of the access hatch, which led up through the pressure hull and out of the vessel. The rocking increased as the sail and then the hull of the submarine broached the surface.

Then the captain barked an order from the control room and the sailor was yanking the hatch open. The sailor pushed the hatch cover up and open as saltwater dripped in and daylight flooded into the previously dimly lit compartment. Now it was the JTF2 team’s turn to act. The sailor pulled down a ladder, which had been stowed against the top of the pressure hull. Corporal Tenny scrambled up and out, followed by Brown. Once on deck, the two men turned and reached back to accept the gear being hefted up by Roy and Strong.

In seconds the two corporals hauled up the compact inflatable raft, silenced outboard motor, and four plastic weapon cases lashed to four water-proofed rucksacks. They then reached in and helped pull first Roy and then Strong up and out into the bright sunlight. The sergeant, coming up through the hatch, took a mouthful of frigid saltwater as a wave broke over the deck, though his black dry-suit otherwise shed the water down into the submarine. On deck now, Strong squinted, and spat out the seawater. After three days sealed in a dimly lit submarine, his eyes hurt as he took in the blue sky, the gray sea, and the submarine’s knife-like black mast towering two and a half storeys above them, forward on the narrow deck. He didn't have time to concentrate on the rolling waves that were breaking against the hull and over the deck. They each had work to do.

Roy attached an air hose, run up through the hatch, to the cylinder containing the raft and the vessel hissed, unfolding into shape. Brown was already attaching the outboard motor as Strong joined Tenny in tossing the rucks inside, securing them to handles on the raft wall using carabiners. Finally, the four men jumped into the raft, which was still perched on the submarine’s deck. Sergeant Strong was in the rear of the raft, manning the outboard motor. Giving the motor a quick rev to ensure it was operational, he looked back at the sailor whose head was poking out of the open hatch. Strong gave him a thumbs up, which the man returned by slamming the hatch shut.

Seconds later Onondaga’s ballast tanks blew and sent white mists of spray into the air on either side of the raft. Then the sub began to submerge by the bow. In seconds it had slipped beneath the waves, leaving the raft and its occupants to bob on the swell.

Strong depressed the outboard motor’s throttle, accelerating past the large the submarine’s still submerging sail, heading northwest towards the gray-green shore. He took a moment to look forward over the backs of his men. Roy was at the bow with his body atop the gear and the other two with a leg each almost dangling into the water to either side. Looking towards the land, Strong took his bearings.

He was wearing a wrist-band compass, which he used to orient himself to the coastline ahead. Strong had spent significant time studying the chart of their intended landing area, memorizing the ins and outs of the rugged shoreline in anticipation of this moment, when he would have to look at the real thing and judge exactly where he was. There. He saw the cove they had selected as their landing point, a small, sheltered area with what appeared now to be a cobble beach. That Commander Hughes really put us right on top of the place, Strong noted appreciatively. He adjusted the outboard slightly and depressed the throttle, making for the cove.

As the small raft with its inflatable sidewalls picked up speed and bucked over the rolling swells, water lapping and splashing over the sides now and then, Strong finally had time to take in the scene around them. The raft was moving through a large inlet with low, rocky, treeless shorelines stretching away ahead and to both sides. To the east was open ocean. Above, the sky was a brilliant blue, and Strong relished the warmth of the June sun on his black dry-suit as he steered. He looked back just in time to see the dark fin shape of Onondaga’s sail silently slip completely beneath the waves.

The swell lessened as Strong steered into the shelter of the cove. A hundred meters from the beach both corporals, Brown, the team’s radioman, and Tenny, the demolitions expert, reached into the center of the raft and unzipped their watertight weapons cases, removing their carbines and aiming them over the bow. Their leader slowed the throttle as the rocky bottom became visible through the pristine water, and then the raft was gently scraping on the stones. Tenny and Brown splashed into the lapping waves on either side of the boat, keeping their weapons high and wading forward the last few meters to dry land. At the same time, Roy stepped out of the bow and began dragging the raft up the beach. After tilting the motor into the boat, Strong jumped out as well and helped him.

With the raft on dry land and the two corporals kneeling nearby to provide security, Strong and Roy unpacked their own weapons, then set them aside on the rocks and unloaded the rest of the gear. The hulking Québécois master corporal took Brown’s position in the patrol’s small perimeter so the smaller man could assemble the team’s radio, an academic exercise at this point as the HMCS Onondaga, the only station that could hear them out here in the wilds of Labrador, was currently underwater. With that task complete, Strong gave a signal and the four men shouldered their loads and moved in a wedge formation up the rocky, mossy headland overlooking the cove.