Story to Book, Part I: How does a story become a scenario?

15 May, 2018 | General News

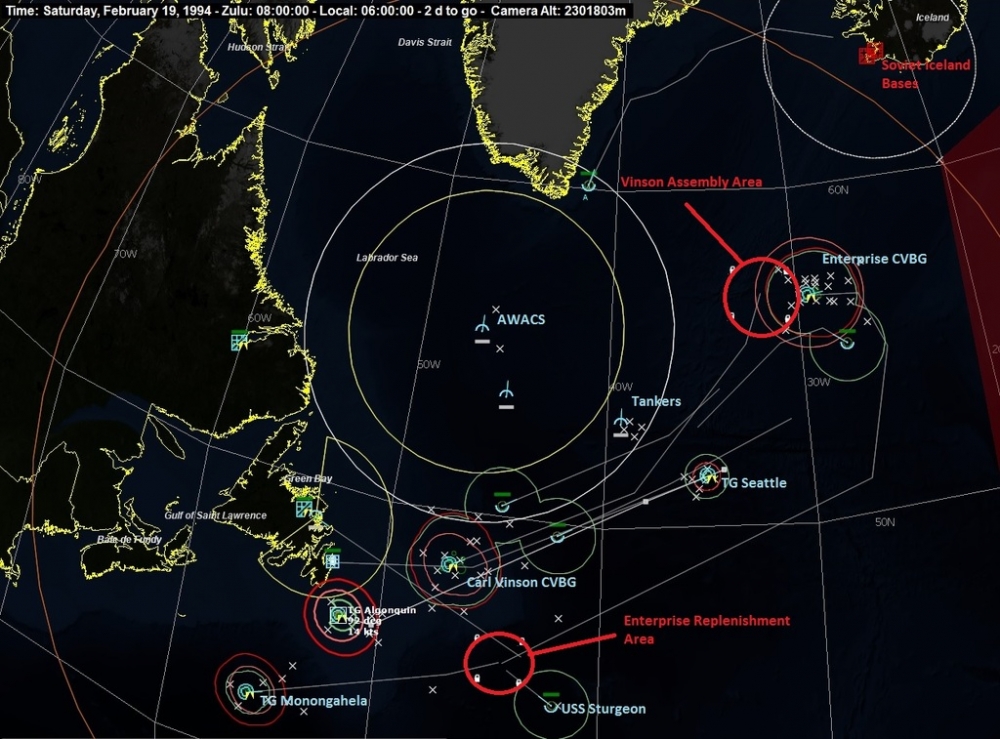

The story of Northern Fury started with me (Bart) right about the time that the Cold War was ending in the early ‘90s. Since then I've been telling the story through scenarios, which today you can find for download as part of the simulation wargame Command: Modern Air/Naval Operations. In this post I discuss how the story makes its way into the scenarios. Later Joel will discuss how the scenarios form the basis for the book series. The whole operation starts with a campaign plan; this takes the form of a “Big Hand, Small Map” approach for both the Soviet and NATO sides. In my office hangs a plasticized map of the globe with red and blue arrows on it. I also have a timeline, various spreadsheets, and (in “Army” jargon) a set of synchronization matrixes. Some of these are printed, some are lost in files on Bart’s computer, some are on Google Docs, and some of them even match!

(Gentlemen, please, no fighting in the War Room)

Before the story can take shape, we have to deal with the two irrefutable constants of Geography and Time. This involves systematically thinking through how one would plot out a global war from the point of view of the protagonists. This “Big Hand” part didn’t happen over a weekend; rather it involved a long process of reading, experiencing life in the Cold War, and thinking through how such a conflict would have unfolded. So there is a plan, or more correctly three plans:

- The Soviet plan with an object of causing NATO to disintegrate as an alliance;

- The NATO plan to recover from the “Bolt from the Blue” attack and end the war intact; and

- The plan for what will actually happen in the overall story (remember, no plan survives first contact with the enemy, or the writing process!). So, given that everything so far is either in my head, on a wall map, or in various disconnected notes, the real story production starts with the scenarios. Some of the original play-testers may recall that the first scenarios produced were not necessarily in order. That’s because we needed to establish some key anchor points for the story before we sorted out the rest of it. Now however, most of the scenarios are being built in sequence, at least by theatre. So how does a scenario start? The Scenario: It starts with a few questions such as: • Where does this segment of the story fit in the overall campaign? Is it pivotal, critical, background or simply fun and interesting? • Is there enough actual conflict to create a scenario? • How does it link to other scenarios around it? • Who needs to win? What needs to happen to further the story? Next comes the groundwork. Even though Northern Fury is alternate history, it still needs to be grounded in real history, so: • What are the likely forces involved? • What forces have been involved in previous scenarios? Have taken casualties? • What is the logistic situation? • What divergence from real history (if any) will the forces portray (new units, technologies, people or actions)? • How are nations or elements likely to react to events, both before and during this scenario? After this comes scenario design: • Lay out the “order-of-battle” for the various sides. Once this is complete, it’s easy to adjust or delete later.

_(That? That's not an order of battle. Now this, _this is __an order of battle)

• Consider the player – what problems will they need to solve to succeed? What decision will they need to make? What are their options? • Consider the complexity – the more complex the scenario, the more it will intrigue experienced players, but may also drive off novice players. • Consider the difficulty – in some ways I approach this like a D&D campaign. One scenario in ten should be almost overpowering, five out of ten should be difficult, three out of ten should be fairly manageable, and one should be quite easy. This is not a science; difficulty breeds re-playability, but also scares off the novice. • At this point it’s worth comparing the ideas with existing scenarios in the series; is there enough difference to make it interesting to the player? • What sort of twist should the player have to deal with? Every scenario, or at least most, should unsettle the player’s plans at least once, force them to make more decisions, reallocate resources, or something along those lines. • How will logistics affect the player? This isn’t a factor in every scenario, but in most it is. Ammunition is the most obvious constraint, but aircraft maintenance, refueling at sea, air-to-air refueling, replacements, even upgrades in some cases come into play. The player should not be allowed to forget about logistics.

/arc-anglerfish-arc2-prod-mco.s3.amazonaws.com/public/MNEJFUS3VBDCPEZTYSZTPIKLG4.jpg)

(Many "meat-eaters" like to hand-wave logistics, at least until they run out of things like ammo and ice cream)

• Communications is next, though not in the classic sense, although the “advanced communications module” is now part of Command. The real trick is to force the player to remember that communications matter in wartime. First and foremost, the player cannot be the “King of the World.” In the bigger picture, there is a boss out there who should make himself felt; there are other battles going on that the player needs to know about; the enemy has a vote. This all boils down to a constant drip of information that the player receives through messages, units (ones that are not under the player’s control) going about their tasks, neutral and allied forces conducting simultaneous operations, etc. The player should feel that their particular battle is part of an ongoing campaign, and should also feel some pressure to do their bit for the overall effort, in the context of the overall plan.

(Let's hope we don't have to pull these out to coordinate an Alpha strike on Iceland)

• Another question we ask is: how do the book’s characters fit into this scenario? Although this isn’t an overriding concern, if there is an easy fit we build our characters in from the start (can you find them, oh play-tester?). • The Enemy. The enemy in Northern Fury is often (but not always) the Soviets, mostly because I can be much more flexible with their order-of-battle than I can with be with NATO’s. The real keys to a good scenario are: the enemy must be a challenge while the friendly side must be realistic (down to how much ordinance a carrier or base stores, the exact version, numbers and availability dates of equipment etc.). So perhaps a Mea Culpa is necessary here: I fudge the enemy order-of-battle a bit, sort of, sometimes… So, with that admission out of the way, it’s time to work out the enemy’s game plan. This involves: o Working out what the enemy intends to do and what he needs to accomplish to win. o Determining the assets at the enemy’s disposal. How can he use them? What new technologies or equipment can the scenario showcase? o What advantage does the enemy have and how should he exploit it? o What disadvantage does the enemy have and how should he compensate? o Since I already know what the player’s side needs to do, what can the enemy do to mess that up? This is not a universal principle; sometimes the player and the enemy have divergent aims. The resulting struggle from such a situation can be quite entertaining as both sides try to accomplish their objectives while getting drawn into each other’s plan at the expense of their mission! o Logistics, though less important than for the player’s side, it should be reasonably modeled. o After this, things boil down to mechanics: Loadouts, missions, events, timings etc.

(The enemy?)

• A side note: to address a question that is often asked (usually by people who don’t actually design scenarios): Why don’t you make both sides playable? Well, the short answer is that I sometimes do, but mostly don’t. To make a good two-sided scenario, in my opinion, takes about three times as much effort as making a one-sided game, not to mention probably four times the playtesting effort. In the end the results are often mediocre. The complexity of designing a rich scenario experience is tricky. Building it from both sides is hard and time consuming. Those who want two sided scenarios are more than welcome to make them, and I see real merit in that. But very few of the Northern Fury scenarios will be, and the ones that are will be the smaller and less complex ones. • The Briefing. I spend a lot of time crafting the briefing. Some players complain that the scenario briefings are too long, but I find that most people like them. Some things that I like to do with the briefing are: o Make sure the basic 5W’s are answered (who, what, where, when and why) while avoiding the How. Let the player figure that one out. o Mix up the briefing format from scenario to scenario. Some tasks arrive as messages, some come through face-to-face meetings with the characters (sort of a novel within the game), some arrive via phone or radio conversations, and a few come just through the commander (the player) looking at their notes. This part isn’t that important, but it does spice things up a bit and create some “atmosphere.” o I try to leave some ambiguity, but also give some clues… sometimes. o I try not to give players everything on a silver platter. Some players don’t like this approach, and it is a fine balance which I don’t always get right. To my mind, playing a scenario is a more enjoyable experience if the player is involved. Forcing them to read implications and problems between the lines in the briefing is a way of involving them. However, for many Command players, English is their second or third language, so subtleties may not be obvious. o Give the player the sense that the part they are about to play is important to the overall war effort.

(Briefings...)

• Testing, tweaking and tinkering. This can go on a long time before it gets released to the forum for testing, and includes setting the scoring criteria. Scoring has been discussed on the forums a bit and it is perhaps worth its own blog post. It can be complex or simple. Some players don’t pay any attention to it, while others really care about their scores. Well that’s it! Simple, right? The Big Point of all this is that a scenario is a story that the player gets to discover as they play. The more thought, depth, challenge, nuance, and atmosphere in the scenario, the more it will draw the player in and get them thinking like a person in the story. From my perspective, this makes for a more enjoyable gaming experience overall. Thanks for reading. In Part II, Joel will discuss how we take these scenarios and turn them into the books of the Northern Fury universe.