Northern Fury 7, Keflavik Capers

AAR By Joel Radunzel

Post 1

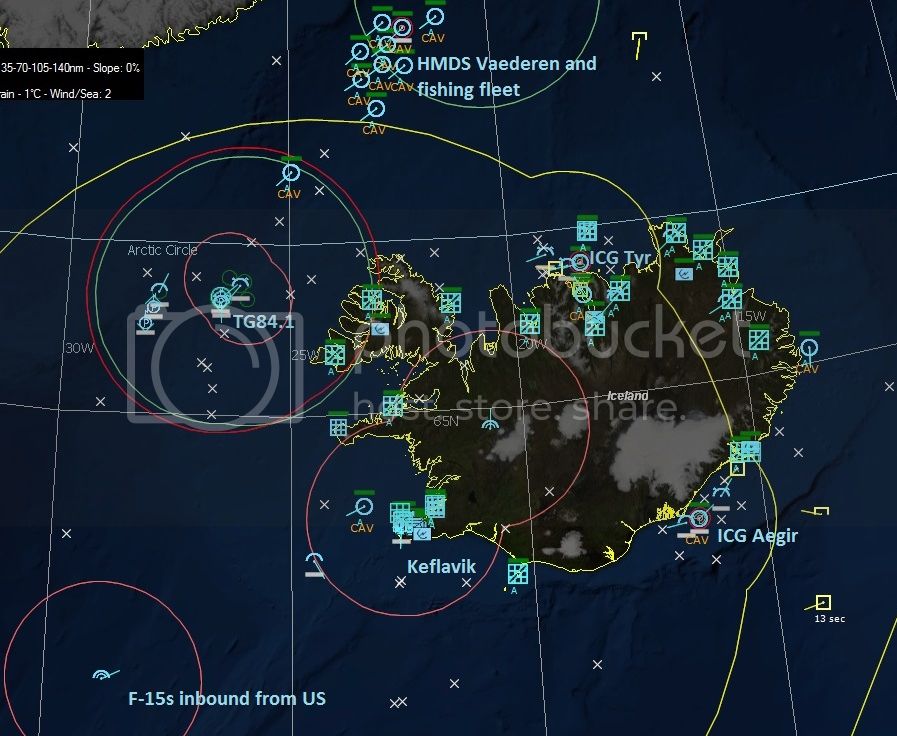

Ok, here’s the latest installment in the Northern Fury AAR series. Here’s the setup: There’s some serious business going down in Norway around Trondheim. Jan Mayen was seized in a coup de main yesterday and one Kuznetsov battle group and one Kiev battle group are likely headed towards us here on Iceland. The airfield at Keflavik was shut down yesterday by a major missile attack in which five missiles got through our defenses to destroy two F-15s on the ground and cratered the runways. We’ve got two AMRAAM-capable replacements inbound from the States, but the rest of our squadron of Eagles are older variants that can only carry AIM-7s. The runways are now repaired. There are also a pair of AWACS, some P-3s, some SAR C-130s and HH-60s, and an assortment of other transports and support aircraft parked around the base. The base is defended by one Patriot and one Hawk missile battery. Effective, but their ammo is not limitless.

All of the US carriers are out of position right now, leaving a small ASW group, TG 84.1, in the Denmark Strait patrolling for the expected surge of Soviet subs. This group consists of the Spruance-class destroyer USS John Rogers accompanied by one US and one Canadian frigate. Further south is the cruiser USS Vella Gulf, which is escorting the LPD USS Trenton back to the US from Europe. The HDMS Vaederen, unlikely survivor of the attack on Jan Mayen yesterday (see my Cold and Lonely Place AAR) is still shepherding the fishing fleet south. The only other naval strength in the area are two Icelandic Coast Guard cutters, the Tyr and the Aegir north and south of Iceland respectively.

Military families and dependents are being evacuated from Keflavik as quickly as they can be loaded on the C-5s and C-141s parked on the ramp. The Icelandic government is conducting a far larger evacuation of citizens from the outlying towns around the perimeter of the island, moving them to Reykjavik in anticipation of sending at least the women and children on to North America in chartered flights. There is a cruise ship, the SS Arctic Traveler, which has already taken a load of 2,500 evacuees out of Reykjavik, and several charter flights are scheduled to depart shortly.

Our mission is ill-defined right now. We don’t know if the Russians are coming our way but I suspect they are. If so, we likely won’t be able to hold, not with a Kuznetsov and its air wing of Su-33s to contend with. Let’s dive in and see how the situation develops!

Post 2

The air control party at NAS Keflavik nervously scanned their threat boards as the E-3 AWACS circling southwest of Iceland fed them data. Signs to the north were growing increasingly troubling. The airborne radar had not picked up any bogeys yet, but threat receivers were reporting Russian radars in action up that way. Outside on the tarmac several C-5s and C-141s were prepping for take-off. Families from the base's garrison were boarding the big transports for the flights to Maine and Canada, out of harm’s way. The wives and children shivered as they crossed the icy pavements to board the uncomfortable military aircraft. Getting those hulking jets off the ground was both a military and a personal priority for the entire base.

As the first C-5 began its painfully slow takeoff down one of Keflavik's long runways, the technicians on the E-3 were also tracking numerous small charter aircraft taking off from the small airstrips that serviced the communities around the perimeter of the island, bringing civilians from these outlying towns to the capital of Reykjavik, where chartered airliners were waiting to carry many on to Greenland and North America. Inter-continental passenger flights were also passing over Iceland, following the great circle routes from Europe to North America.

As the Air Force monitors tracked these movements, ominous signs began to develop to the north of Iceland's northwestern Westfjords Peninsula. Pairs of aircraft were approaching, one behind another. These were quickly identified as Su-33s by their radar emissions. Somewhere beyond them then was one of the Kuznetsov-class carriers. More pairs continued to appear on the screens of the AWACS controllers and in the military radar facilities that dotted the perimeter of Iceland, until they were tracking a full eighteen Soviet fighters. Only two F-15s were currently orbiting over central Iceland, and the air controllers immediately ordered the other two ready flights into the air. A Soviet sweep of Icelandic airspace seemed imminent, and the idea of high-performance interceptors in and among the lumbering transports departing Keflavik was a nightmare for more reasons than one.

The lead Soviet pilots banked their naval fighters into a holding pattern off Iceland's north coast, allowing the full weight of the Russian squadron coming behind them to assemble before they began their sweep. The six American Eagle pilots and their airborne controllers had little time to set up an ambush to try to offset their three-to-one numerical inferiority before the Russians came charging south. Knowing that the Russians lacked any long-range surveillance radars, the air controllers decided on some misdirection. All of the American fighters would approach with their own radars off until the time came to launch their long-range Sparrows. This would hopefully allow the Americans to attack from multiple directions and minimize the Russians' situational awareness. A second, backstop ambush could also be sprung if the Russians were aggressive enough.

As the full weight of the Soviet sweep turned south, the pilots of four of the F-15s went to military power and approached the enemy formation from the southwest. When the AWACS controllers reported they were in range, the Eagle jocks flipped on their radars, each acquiring one target, and loosed a volley of eight AIM-7 Sparrows at the distant Russians. The elite Russian pilots responded immediately, turning into the threat and going to afterburner to close the range. But the Sparrows had longer legs than the Russians' R-27s (NATO reporting name AA-10 Alamo). Both weapons, however, had the disadvantage of being semi-active radar homing, meaning the launching aircraft had to keep its radar pointed at the target for the missile's entire flight.

The Sparrows flashed into the oncoming formation of blue and grey painted Soviet jets. The notoriously ineffective AIM-7s did well, exploding into the paths of the oncoming Soviet pilots who had just launched their own missiles. Three of the four double-target Su-33s were shredded, the pilots killed in a cloud of shrapnel. Now the American pilots banked violently and punched their afterburners, fleeing before the volley of approaching AA-10s. Several of the Russian missiles had been launched by pilots and jets that were now tumbling into the north Atlantic. These lost lock and continued on harmlessly. Many more, however, continued to close the distance to the fleeing F-15s.

The Americans almost managed to escape the counterattack unharmed, but one R-27 at the end of its range exploded behind the rearmost Eagle, shredding its port wing and engine and sending it into an uncontrollable spin. The pilot did not eject.

The Soviets continued to pursue, but now the Americans sprung their trap. The other two F-15 pilots had been quietly approaching from the southeast. They now flipped on their radars and launched four sparrows into the flank of the Russian formation. The Sparrows' 50% accuracy was barely enough again to blot two Su-33s from the sky. Now, however, the Russians' advantage in numbers began to tell. Half of the thirteen surviving Russian pilots continued to pursue the three F-15s fleeing to the southwest, while the rest turned and counterattacked the two flanking Eagles with another volley of R-27s.

The two American pilots turned and burned, following the same tactic as their comrades to the west, but it failed to save one of them from being smashed by shrapnel from an exploding Russian missile. The score now stood at five Sukois splashed against two F-15s. The Americans pushed their interceptors to the limit now, streaking south towards Keflavik with the Soviet flyers in hot pursuit. The geometry of the engagement allowed the Russians to barely catch and bring down a third Eagle as the battle passed over Reykjavik. Two more Eagles rocketed down the Runway at Keflavik as the action drew near, but the advantage appeared, at least to the Russians, to be entirely in the favor of the attackers at this point. The NATO defenders, however, had an ace up their sleeve that the Soviet pilots, in their excitement, had failed to account for.

Post 3

The air defenses around Keflavik had remained silent as the aerial drama closed to within 70 kilometers of the base, and a C-141 rumbled down the runway, its crew hoping to escape before the coming drama unfolded. The surviving F-15s, with the Su-33s pursuing, were making a straight line for the runways, while remaining at thirty-six thousand feet. Then, as the fight closed to within 40 kilometers of the airfield, MIM-104B PAC1 Patriot missiles exploded out of their boxy canisters east of Keflavik. The deadly weapons streaked upwards at Mach 4.1.

Too late, many of the Russian pilots realized their peril. Adding to their danger were the two Eagles which had just taken off, which added their Sparrows to the mayhem unfolding in the Soviet formation. The Patriot and Sparrow missiles combined to smash seven of the Soviet fighters before the remaining six were able evade their way out of the deadly kill zone of the Keflavik defenses, but not before one more Eagle was destroyed by an R-27, the pilot ejecting directly over the base as horrified family members looked on below. The loss ratio now, due to the Soviets' blundering into range of the Keflavik SAM batteries, was four F-15s to twelve Flankers.

As the surviving Russian pilots withdrew to regroup and circle over central Iceland, two more F-15 pilots pushed their throttles forward and rocketed down Keflavik's runway. The intervention of the SAMs had evened the odds. Now six F-15s could venture out from the safety of Keflavik's Patriot and HAWK launchers to go toe-to-toe with the six remaining Sukois. The Americans, smarting from the quick loss of four of their comrades, were out for blood, and their numerical parity now allowed them to take advantage of the longer range of their Sparrow missiles.

The Soviet flyers were stunned by the loss of two thirds of their number in their flight across the island. Their response to the new American sortie was ragged. The Eagle pilots had spread out, with one flight approaching the Russians from three different vectors. Missiles began to leap off the rails of the opposing jets, American first, then the shorter-ranged R-27s. Both sides' weapons performed poorly, but the ability of the Americans to engage at long ranges proved decisive. The Russians died or were forced to eject one by one, until the airspace over Iceland was once again patrolled by NATO fighters only. One more Eagle was lost in the battle as well.

For the loss of five precious F-15s, eighteen Sukois had been downed. This represented a large portion of the air group on the Russian carrier that was lurking to the north. The AWACS was tracking more Su-33s as well as flights of Yak-141 Freestyles (indicating the presence of a Kiev-class carrier group as well) patrolling north of the island, obviously blocking any NATO planes from getting close enough to see what the Soviets had up there. But they were not coming south, and the Americans were happy to let them alone. Two Mig-23s out of the newly captured field at Jan Mayen had tried to interfere in the end game of the dogfight over central Iceland. One had been shot down, but the presence of that airfield was another worrying portent.

Even worse, the NATO pilots were almost completely out of Sparrows now, and the remainder of the squadron was still readying in their hardened shelters at Keflavik. This, just as the ground-based radars scattered along Iceland's coast began to pick up formations of bombers approaching from the north, northwest, and west of the island.

Post 4

While the drama above had been unfolding, charter flights from the outlying towns and villages around Iceland were converging on Reykjavik like the spokes of a wheel, while MAC flights out of Keflavik and airliners out of Reykjavik took off for Greenland and Bangor, Maine, as fast as they could be filled with passengers. The Icelandic government was not going to be caught with much of its most vulnerable population in the crossfire of World War III. Some of the evacuees were leaving by sea, however, borne by the Icelandic fishing fleet.

One of these ships, a commercial trawler out of the port of Akureyri at the head of the Eyjafjordur on the north coast, was observed by the radar on the ICG Tyr to reverse course halfway up the fjord and head back towards Akureyri at twelve knots. The captain of the Tyr, knowing that the boat should be evacuating civilians from the port, attempted to reach the craft by radio to determine if there was an emergency. When he got no response, he ordered his own vessel into the fjord to investigate.

Moments later, the Tyr's captain received a frantic call from the airfield mechanic on Grimsey Island, a speck of a landform off the north coast of Iceland which contained a village of eighty-five inhabitants (all evacuated save the mechanic), a small airfield, and not much else. The mechanic breathlessly reported that three armed men in civilian clothes were moving from building to building as if searching for something. Then there was an explosion, and the line went dead.

The Tyr's captain passed the report on to Reykjavik, unsure what to make of this development but thankful that the population of Grimsey was safely in Reykjavik. His cutter continued in pursuit of the southbound fishing trawler, which still failed to answer his hails. He ordered his helicopter, already aloft and doing a surface search at the fjord's mouth, to enter the fjord and look over the small ship.

On the positive side of the ledger, the two MSIP F-15 Eagles sent from the States to replace yesterday's losses in the missile attack had landed, and the ground crews went to work frantically removing their Sparrow armament and replacing those missiles with the far more capable AMRAAMs. Provided they could be rearmed in time, these two birds would supply a nasty surprise to another Soviet sweep. But the Soviet bomber crews weren't willing to wait for the American fighter pilots to take wing again. NATO radars began to detect small supersonic objects detaching from three approaching bomber formations, heading towards Iceland.

Post 5

As the supersonic Kh-22P missiles ignited under the wings of the approaching Tu-16 and Tu-22 bombers, Keflavik began to prepare for another round of the treatment the airfield had received yesterday. However, the radar operators in the picket line around Iceland quickly realized that the targets of these missiles were not the airfield facilities, but rather the radar picket line itself.

The big Soviet radiation-seeking missiles streaked in from the north and west. The first radar destroyed was the one covering the northwest peninsula. Its crew had been too slow to shut their radar down, and the technicians paid for their mistake with the destruction of their powerful sensor. The crew of the radar on Iceland's northeast was able to switch off their systems in time to confuse the Soviet weapons, enough so that the Kh-22 fired at this site crashed into a snowy hillside more than a mile beyond. Warned by the other attacks, the radar crew on the southeast coast of the island shut down their sensor as well, foiling the Soviet attack on that site.

The Soviets had suppressed the radar net, however. Two more formations of Tu-22s, coming in behind the first two northern groups, now loosed stand-off missiles of their own, this time aimed at Keflavik. The big weapons lofted into a supersonic ballistic arc, headed south.

The technicians on the E-3 flying racetrack patterns to the southwest of Keflavik tracked the inbound wave of missiles as they neared their targets. As the Russian weapons closed within seventy kilometers PAC-1 missiles once again streaked out of the SAM battery's boxy launchers and arced northward.

On the tarmac, airmen were scrambling to get the military families still waiting to board a MAC flight into shelter before the missiles struck. The Patriots almost prevented this from ever happening. The air defense missiles did well, knocking down most of the incoming threats, but the earlier engagement with the Soviet fighters had expended a large proportion of the battery's ready missiles, and as the last PAC-1 container emptied it became clear that there would be leakers. The shorter-ranged HAWK battery was poorly positioned to intercept any more.

Three missiles made it through the defenses. Two plowed into the end of the runways and exploded, throwing snow, ice, dirt and concrete out of two deep craters. That runway would be closed until those craters could be repaired. The third missile plowed into a empty hardened aircraft shelter, shredding the remaining equipment inside the structure but otherwise doing no damage. The all clear began to sound around the base, then abruptly ceased as another wave of missiles, launched by the second group of Soviet bombers, was detected by the E-3's radar.

The control tower at Keflavik had been working to get every possible aircraft off the ground at the start of the Soviet missile attack. This resulted now in several F-15s orbiting over the base as tankers and MAC flights rumbled down the one operational runway, took off, and banked to head southwest. The Patriot battery had expended all of its ready missiles and would be out of the fight until these could be replaced. As such, the controllers on the AWACS ordered the Eagle pilots over Keflavik to use their missiles to engage the incoming Russian weapons. A pair of F-15 pilots had attempted to intercept the missiles of the first wave mid-flight, but the Russian weapons had been too high and too fast for an effective Sparrow engagement. All hoped that intercepting the missiles at their destination would prove more fruitful.

The Russian missiles nosed down over Reykjavik and began their terminal dive towards the NATO base. The American fighter jocks, circling at low altitude south of the airfield, turned north and formed into a picket line to engage the incoming threats. As the Russian missiles dove down through 40,000 feet the Americans began to launch AIM-7s and then AIM-9 Sidewinders as the vampires drew closer. The Sparrows proved more effective against the straight flying missiles than they had against the maneuvering Soviet fighters, but even so the engagement window was very small and two of the incoming Kh-22s got through. This had apparently been intended to hit at the Keflavik munitions reserves, as both missiles plowed into ammunition revetments and exploded. In each case, the Russian weapon penetrated the frozen earth around the ammunition facility but failed to penetrate the concrete inner shell. Base firefighting teams rushed to both impact areas and extinguished the fires before they could cause further damage. The cratered runway, however, would take more time to repair. Above, the American fighters turned north to intercept Russian bombers, which were following the missiles in over northern Iceland.

Post 6

The US fighters flew north and northeast, low on missiles after their defense of Keflavik. Two groups of Soviet bombers were approaching from these vectors. One was set upon by a pair of Eagles whose pilots performed a high-speed head-on approach, launching Sidewinders and then 20mm cannon rounds into the oncoming Tu-22Ms, sending four of the supersonic jets trailing flame and smoke into the snowscape below. The pilots of the northeast group of approaching bombers, realizing their fighter screen had been destroyed, turned back, and accelerated out of range before the Americans could close with them.

As the air battle lulled, more troubling signs began to arrive at the Keflavik base HQ. With the ongoing attacks and damage to one of the runways, the evacuation of military families and non-essential base personnel would only be mostly complete by nightfall, though MAC flights were again rumbling down the one operational runway, passing frantic efforts to repair the craters in the other. In Reykjavik, the Icelandic government reported that they would still have 35,000 civilians to evacuate by the next day, despite a constant stream of charter flights leaving the city's airport.

As if the situation wasn't complicated enough, with MAC and charter flights leaving the island, small aircraft and helicopters bringing evacuees to the capital from the rest of the island, international flights still passing overhead, and intense air combat in the skies throughout, now another message arrived at Keflavik HQ. Danish Air Transport (DAT) flight 745 out of Copenhagen, which had been diverted from its original destination in the Faroes due to a threat there, was reporting an emergency and requesting permission to land at the Hornafjordur airport on the south coast, near one of the NATO surveillance radars. The Icelandic Coast Guard granted permission, and the plane approached. Most of the F-15 pilots had been directed to return to base to rearm, but one of the two remaining airborne teams was vectored to escort the civilian aircraft in.

Minutes later, another troubling call came in from Bakkafjordur on the east coast of the Island. Before being cut off, the caller had reported a surfaced submarine in the harbor and several boats with armed men in them making for the shore. At the same time, the Icelandic Coast Guard called saying that they had received a cell phone call from aboard DAT 745 reporting that the aircraft had been hijacked and that the flight crew were dead. In the confusion, the air controllers were forced to decide if the aircraft, full of civilians as well as enemy combatants, apparently, should be shot down by the escorting Eagles. In the end, the commander at Keflavik elected to leave the aircraft alone until the situation became clearer.

Then an official phoned again from Bakkasfjordur, reporting that armed troops were taking control of the town, its port facilities, its airport, and also that a group of the invaders had departed the village in captured vehicles at high speed. Clearly the Soviets were making a play to capture the Island's outstations. Their game became clearer in the coming minutes.

Post 7

Over the next hour, the list of locations under attack by small groups of Spetznaz and Naval infantry grew ever longer as the Soviets seized one small airstrip after another along the north and west coasts of Iceland. DAT 745 landed and immediately disgorged five men armed with AK-47s and explosives who took control of the tower at Hornafjordur. In Reykjavik the telephone exchange and broadcasting station came under attack by teams of Soviet special forces. The base commander at Keflavik dispatched a platoon of Marines to assist the Icelanders in the fight taking place in the streets of their capital. The suspicious fishing trawler that that had reversed course in the Eyafjordur entered the harbor at Akureyri and uniformed Soviet naval infantry began unloading boats.

The ICG Tyr was still too distant to interfere, more than halfway up the fjord, but its embarked helicopter came close for a look at the ongoings. As the aircraft completed its second circle of the site, reporting on naval infantry climbing down into the boats, a team of two soldiers dashed out of the trawler's superstructure carrying a long tube. One soldier knelt, oriented his weapon upwards, and launched an SA-7 SAM at the coast guard bird. The Icelandic crew never had a chance. The shoulder-launched missile exploded feet from the craft, spewing hot shrapnel that shredded the small helicopter, which dropped burning into the dark icy water below. Nearby, the Soviet assault force sped towards the Akureyri port facility in their high speed RHIBs.

Closer to Keflavik, the Rockville radar station at the point of the Keflavik peninsula came under mortar fire. Another of the airbase's defense platoons was dispatched to sweep the area west of the airfield. They blundered into a Spetznaz unit shifting their mortars from one target to another and a fierce firefight ensued. The American security force was able to pin down the Russians, but the rest of the airfield's defensive force had to converge on the threat before the last Soviet commando was killed.

In quick succession, the towns of Hofn, Vopnafjordur, Husavik (with a 1600m runway), and Sauderkrokur all reported approaching small teams of armed men before going off the air. And more ominous signs were developing in the skies northeast of Iceland. Two more bomber formations were approaching, as well as several pairs of slow moving contacts from out of Jan Mayen that could only be transports. The ground crews at Keflavik had managed to rearm several F-15s, and the pilots of these jets now taxied back on to the one available runway, punched their afterburners and rocketed upwards to once again defend the Icelandic sky.

The ICG Tyr finally arrived at Akureyri harbor. Enraged by the loss of his helicopter and its crew, the captain of the cutter ordered his machineguns and 76mm cannon to engage the trawler and the RHIBs. Shot peppered the fishing boat, shredding the superstructure, and machinegun fire destroyed two of the four RHIBs. But the Tyr was not a warship, and ammunition began to run low rather quickly. That fact, and some ineffective RPG return fire from the Russians ashore, convinced the captain to withdraw back up the fjord.

Anticipating another missile attack, the air controllers on the AWACS opted to keep the airborne F-15s orbiting at low altitude directly over Keflavik. The Patriot battery only had six missiles remaining. These were now all loaded onto the launchers, but wouldn't be enough to defeat another wave of the supersonic Kh-22s, and the HAWK battery had yet to successfully intercept a single missile. The Americans lacked the numbers to both protect the base adequately and venture out to intercept the approaching pairs of light transports from Jan Mayen. Indeed, the crew aboard the E-3 watched their scopes helplessly as a Yak-141 flew over northeast Iceland and destroyed the radar site that had managed to evade the longer ranged ARMs launched by the first wave of bombers.

As the situation was developing, a Flash message came in from US 2nd Fleet HQ. The Admiral had been monitoring the ongoing battle on Iceland and elsewhere. Prompted by the attrition among the F-15s as well as the Soviet occupation of many of the communities on the north and west sides of the Island, the message ordered the commander of Keflavik to immediately begin evacuating the base and destroying its stores and infrastructure. A major Soviet airborne assault on the island was expected within the next several hours, and the Admiral did not believe NATO had the strength to hold.

As such, TG 84.1 would pull off its ASW patrol in the Denmark straight and proceed to the Keflavik peninsula to provide air defense for the evacuation. The LPD USS Trenton, transiting south of Iceland, would change course and steam north to take on the base's helicopters. Darkly, the Icelandic government would not be informed of the evacuation until it was nearly complete. The base commander finished reading the order as klaxons sounded once again. The incoming Soviet bombers had released another wave to Kh-22s...

Post 8

The Russian missiles came on as before, lofting into supersonic arcs that nosed over to dive onto the remaining operational runway at Keflavik. If this strip were sufficiently cratered it would trap a large number of aircraft, tankers, a priceless E-3, the remaining MAC C-5s and C-141s, several Air Force and Coast Guard C-130s, a pair of P-3s, and the remaining F-15s on the runway. The crews of all of these were frantically preparing their aircraft for the evacuation, but it would all be for naught if the Russian missiles got through.

As the Soviet weapons closed, the remaining six PAC-1s rocketed from their launchers, destroying half of the inbounds. Now it was the Eagle jocks' turn. They banked their fighters north, lit off their radars, and launched AIM-7s and AIM-120s from the MSIP birds that had finally gotten off the ground at the incoming missiles. All the Kh-22s were downed but one by the radar-homing missiles. This last one dove at the Keflavik runway. Just as it was tipping over into its terminal maneuver, an AIM-9 from one of the F-15s exploded above it, dropping wreckage of both missiles onto the base perimeter fence. The missile attack had been defeated, but once again the airborne American fighters were low on missiles.

The AWACS controllers vectored the four best-armed F-15 pilots to intercept the small transports that were approaching the airports at Akureyri and Hofnafjordur. Other transports were already landing at some of the more distant towns that had been seized, but these were beyond the capabilities of the American pilots to intercept at this point.

Over Akureyri, four Mig-23s out of Jan Mayen attempted to interfere with the American intercept. Two fell to the American's remaining Sparrow missiles while the other two engaged in a brief dogfight with one of the Eagle pilots before withdrawing. The other American swooped down on the hapless An-24 light transports. Sidewinder missiles connected with both aircraft, in each case exploding against one of the engines and causing the thin wing to fold. Both An-24s, along with their crews and a platoon of elite Soviet paratroopers, plunged into the snowfields south of Akureyri and exploded.

At Hofnafjordur, the intercept was less successful. A raid of Tu-22Ms was inbound on the same vector as the transports, and the NATO fighter pilots had to choose between engaging these and going after the transports. They chose to protect Keflavik, as holding Iceland was a lost cause now, the mission being to get as much out as possible. The Eagles tore into the bombers head on, downing several in a single pass. The others turned and fled, leaving the Eagle drivers free to attack the transports inbound to Hornafjordur. But it was not to be. The distraction of the bomber raid had been just enough to allow the Soviet transport pilots to advance their throttles and make a fast descent into the small airfield. Both turboprops made safe landings, harder than their occupants would have liked, and taxied to the tower.

Before the planes even stopped the doors opened and Russian desantniki began dropping onto the tarmac below. They linked up with the KGB officers from the DAT flight who provided them with seized vehicles, and a squad immediately took off for the nearby surveillance radar, which even now was being destroyed by its NATO crew.

Other Soviet desant platoons put down all over the northwest arc of Iceland on captured airstrips with less drama than these two locations. The Americans were simply spread too thin defending and evacuating Keflavik to interfere. The Admiral's judgment on NATO's ability to hold the island was looking ever more accurate as time went on. The numbers of invaders were relatively small, but there was nothing to oppose them. In Reykjavik, the attackers at the telephone exchange and TV station had withdrawn when the USMC platoon arrived, but the American platoon leader could not exploit his success, being ordered without explanation to return to base. The Icelanders watched them Americans leave in growing confusion and concern.

South and west of Iceland, the P-3s from Keflavik began dropping sonobuoys to sanitize a path for TG 84.1 and the USS Trenton, escorted by the cruiser USS Vella Gulf to approach the southwest peninsula. Two Soviet subs, an Alfa and a Sierra, were detected transiting the Denmark straight in TF 84.1's wake, but the Orion crews didn't have enough fuel to both protect the NATO ships and prosecute the contacts and still make the long flight to Bangor, Maine. These Russians would make it into the Atlantic. Keflavik commander, who was keeping his Gulfstream as the last to depart the base, hoped to inflict at least some damage on the anticipated Russian paratroop drop. He ordered all of his fighters back to base to rearm in the hope of having a sizable force to put into the air when the time came.

Post 9

The Soviet planners had not intended to give the Americans time to concentrate their fighters against the massed transports carrying a regiment of the 76th Guards Airborne Division to Iceland. Shortly after the last Eagle pilot landed his fighter on Keflavik's open runway troubling signs began to appear on the screens watched by the technicians in the AWACS. Electronic jamming began to fill their scopes covering the eastern edge of Iceland. The monitors deciphered the unique signatures of at least two of the potent An-12 EW aircraft that had been causing NATO fliers in Norway so much trouble. Through the jamming haze they could also make out the signatures of powerful radars mounted on multiple Mig-31 interceptors. NATO pilots had learned to respect these aircraft and their long-ranged R-40 (AA-6) missiles.

While the situation to the east of Iceland was developing, the base personnel at Keflavik did their best to get every person possible off the island. The remaining military family members were crammed aboard the last few MAC transports without regard to comfort or even safety. Once these aircraft were gone, the remainder of the base's personnel began to board the KC-135s, the remaining E-3, a P-3, and SAR C-130s that departed the base as quickly as they could be readied. Three C-130s were reserved for the base defense personnel who, having eliminated the Spetznaz threat to the west, were now busy destroying as much equipment as possible to prevent its capture by the Russians, and the ground crews who were preparing the surviving F-15s for one more mission from Keflavik before they made the long flight to Goose Bay, Canada. Tankers from the US would meet them over Greenland to refuel en route.

Even before any Soviet transports began to appear on the scopes of the NATO radar operators, events conspired to weaken the blow they would be able to land against the paradrop. Two Soviet reconnaissance Tu-16 bombers were working their way around Iceland, one to the northwest and another to the southeast. The northeast Russian was coming dangerously close to detecting the Trenton/Vella Gulf group to the south. The loss of these ships would mean that the helicopters still at Keflavik would have to be burned rather than rescued. To counter the threat, two ready F-15s at the base rolled down the runway and rotated up before banking and settling into a southerly intercept course.

The Russian snooper was descending, apparently to visually identify the two NATO ships in the gathering darkness, when the lead American pilot switched on his radar and launched a single long-ranged Sparrow missile at the twin-engine bomber. The Russians knew they were under attack based on the warbling of their radar warning receiver, but the pilot was unable to locate the incoming missile. The weapon exploded into the Badger at the midpoint of the fuselage. The aircraft continued for a few seconds, then violently folded in half, the pieces falling towards the clouds and dark ocean below.

The Americans now turned their attention towards the second snooper flying south of Iceland. The crew of this one, warned by a distress call from the pilot of the doomed Tu-16, turned back. The Americans, approaching the point where they would not have enough fuel to rendezvous with the tankers, were ordered by their controllers to turn away as well to start the long flight to North America. The Russians had lost a valuable reconnaissance platform and been denied information about NATO ships near Iceland, but the force available to confront the Soviet airborne drop was now reduced by two airframes.

As the skeleton ground crews at Keflavik labored in their hardened shelters to ready the remaining F-15s for one more mission, a large screen of lumbering transports began to appear on the eastern edge of the circling E-3's radar coverage despite the An-12s distant jamming. A full squadron of Mig-31s was also off the coast, interposed between the transports and the American force at Keflavik. The air commander ordered all of his ready jets, six F-15s, to take off and prepare to intercept the Soviets. How they would get past a squadron of eighteen potent Mig-31s to do it, though, was a problem none of them were sure they could overcome.

Post 10

The six American pilots formed up over Keflavik. The airbase was now protected within the edge of the engagement envelope for the SM-2 missiles carried by USS John Rogers, the Spruance-class flagship of TG 84.1. At the base, the US Army Patriot and USMC HAWK crews had already destroyed their equipment to the best of their ability and made their way to the airfield, hoping for a flight off of the doomed island. Four helicopters at the base lifted off, heading for the approaching USS Trenton to the south carrying as many people as each bird could lift. High above, the last F-15 pilot leveled his aircraft off at thirty-six thousand feet and the entire force turned east and accelerated.

The American's plan for interfering in the air drop was both simple and desperate. Four of the Eagles would cross central Iceland, making directly for the masses of Soviet aircraft to the east. The two remaining pilots would drop down to low altitude, turn south, and try to use the rugged Icelandic coast to get in behind the Russian interceptor screen. Four Eagles would have to face the weight of eighteen Mig-31s, and even if they succeeded the two raiders to the south would only be able to disrupt and put a dent into the Soviet drop, rather than stop it outright. But they had to try.

As the American approached, the Russian Mig pilots formed their aircraft into a rough line abreast and pushed their throttles to the max. The Mig-31 was not a maneuverable aircraft, but what lacked in agility it made up for in speed. The big Russian fighters leapt forward, accelerating to nearly Mach 2 as they closed with the oncoming Americans, their powerful radars tracking on the four lonely blips.

The opposing airmen closed with each other rapidly. At extreme range, the four American each selected a target from the multitude on their own scopes and launched two AIM-7s at each. Night had fallen, and shortly after their own missiles had streaked away the American fighter jocks could make out the winking of the wave of return fire leaping off the rails of the line of Russian jets in the darkness ahead. More than a dozen big R-40 missiles arced towards the American jets. The Eagle pilots, RWR warbles screaming in their helmets, gritted their teeth and kept their radars pointed at their targets, willing the outbound missiles to hurry so they could finally evade.

The American missiles exploded into the Russian formation with disappointing results. The extreme range, high speed of the targets, and jamming support provided by the An-12s combined to keep Russian losses to two Mig-31s. Fortunately for the Americans, each of the pilots killed had been directing a pair of the incoming missiles. These now lost lock and flew on harmlessly. The four American pilots now threw their jets into violent evasive maneuvers, trying to outmaneuver the big Russian weapons locked on to them. One didn't make it. An AA-6 exploded into the belly of a banking F-15, destroying both engines and causing the fighter to rapidly break up.

The surviving three Americans turned west and flipped on their afterburners, trying to escape from the oncoming wall of Migs. Now the Russian speed advantage told, as the Soviet pilots were able to close with the retreating Americans and launch a second volley of missiles. The engagement profile wasn't ideal, but one more Eagle was destroyed before the Russians turned back over central Iceland. Their run on afterburner had depleted their fuel, and several jets would have to take on gas from the tankers circling off the coast.

Post 11

The front of the stream of Soviet Il-76 transports carrying a regiment of the elite 76th Guards Airborne Division was now making landfall over the east coast of Iceland. The formation was composed of more than two dozen of the big, four-engine jets, and they were heavily laden with paratroopers, BMD assault vehicles, mortars, artillery, and pallets of supplies. The drop zone the Soviet planners had selected was a broad, treeless plain on the southern coast of the island. The location had the advantage of being astride the Icelandic Highway 1, the road that circled the perimeter of the island. Best of all, it was completely undefended, as was most of the rest of the island at this point.

The pilots of the wide-bodied transports banked right and began to descend to low altitude for their final approach. A Spetznaz pathfinder team from the Hofn landing had set up beacons to guide them into the DZ. This was the point when the transports were at their most vulnerable. Flying low and slow, their paratroop doors open, cargo ramps down, paratroopers standing in long lines to jump, the big jets could not maneuver or evade at this point.

The other two American pilots had been working their way east along the south coast of Iceland at low altitude. When the Soviets had started their sweep over central Iceland, these two turned north, trying to turn the flank of the Russian formation and get in among the exposed transports. Almost immediately their ambush began to unravel. Six of the Soviet Mig-31 pilots had held back from engaging the Americans to the east. They now detected to two ascending Americans to the south and turned towards the threat, pushing their throttles forward to afterburner.

The Americans had no choice but to try to deal with this threat. AIM-7s leapt off the rails of the two fighters, streaking north towards the oncoming Russians. But now the American plan truly unraveled. Several of the Migs that had turned back the F-15s over central Iceland now vectored towards the new incursion, approaching the isolated Americans from the northwest and firing their own R-40s at extreme range.

The two Americans had no choice but to dive for the deck, bank, and evade the multiple incoming threats, leaving their Sparrows to fly off into nowhere in the process. The maneuver failed for one of them. A Russian missile exploded into his aircraft's tail just as he was leveling off several hundred feet above the water, knocking the twin-engined fighter and its pilot into the dark ocean below. His wingman escaped by flying far out over the north Atlantic before turning back west. The Russians, knowing they had defeated the only credible threat to the airborne troops, were happy to let him go, returning to their barrier patrol over Iceland.

The Il-76s proceeded unmolested over the drop zone, where thousands of paratroopers jumped into the dark night, forming long lines of gently descending parachutes. Vehicles and artillery, yanked out of the back of the transports by drogue chutes, descended under three massive chutes each. When these fully crewed vehicles neared the ground, retro-rockets on their drop pallets fired to soften the landing. Minutes after landing, Russian BMD assault vehicles and light trucks rolled off the pallets and moved to where the troopers were assembling. Within thirty minutes columns were moving away from the drop zone in both directions along Highway 1. The drop had been a complete success, the American attempt to interfere a disaster.

Back at Keflavik, the US commander knew now that the security of his base was measured in hours, the amount of time it would take the Russians to move to the southwest peninsula. He ordered every remaining aircraft into the air. The remaining personnel were moved to nearby fishing villages where locals were persuaded to take them onto fishing trawlers that would try to rendezvous with the NATO ships offshore. An American submarine had located the Kuznetsov battle group heading south at 18 kts, meaning that TG 84.1 had precious little time to stick around and pick up evacuees before they would have to flee south.

As the three Eagle pilots who had survived the thrust at the Soviet transports overflew the base, the remainder of the squadron took off in pairs. They all headed west to link up with tankers circling over the southern tip of Greenland to help them on their way to North America. Next the last three C-130s, carrying the personnel deemed least replaceable took off, and finally the base commander walked up the steps to his Gulfstream, entered without looking around, and ordered the pilot to take off. He had managed to get all of his aircraft out, but it was hard for him not to feel he had failed in his mission. With the departure of his jet, the last military presence for NATO left Iceland, which in a few short hours would be completely under the control of the forces of the Soviet Union.